The History and Future of Hyper-Local Radio

Some day soon, Congress may pass the Local Community Radio Act, a piece of legislation that will allow a couple thousand new low-power FM radio stations to go on the air.

The new broadcasters would be much smaller than the stations that dominate the market now, and by law, they'd be noncommercial. Low-power FM (LPFM) transmitters operate at 100 watts or less (drawing about as much power as an incandescent lightbulb), which means they reach only a few miles and are truly local in scope. This means these stations have the potential to occupy a very different niche from large-scale networked broadcasting. Mom-and-pop LPFM stations range widely in terms of programming. KAQU-LP in Sitka, Alaska, broadcasts whale sounds from an underwater mic; various school districts and churches have LPFMs, covering religious, municipal and highly local topics like school board meetings; and other stations provide the sorts of arts and culture programming that have been drowned out in the wave of homogenized content brought about by consolidation of for-profit media companies.

Part of what is so interesting about media made by community members is its potential to challenge what we think radio "is." Our present-day understanding of radio has to a great degree crystallized around the massive network configuration -- both commercial and noncommercial, like National Public Radio. Yet LPFM shows that technology's contours can shift over time based on ongoing renegotiation between players like regulators, corporations, advocates and everyday citizens. Far from being a moribund medium, radio can have an alternate future -- one that actually reawakens long-forgotten debates that were "settled" shortly after the dawn of broadcasting.

In fact, radio provides a somewhat rare opportunity to think about technological change over time, and in many ways the issues surrounding it now are not so different from those present at the dawn of broadcasting in the 1920s. Then as now, a large part of what defined the technology was decided through heated contestation between groups with competing visions for its use: Should radio stations be networked and strive to reach a wide and dispersed audience? Should they be commercial and profitable, or operate on a non-profit or community-subsidy model? Should they serve the "public interest", whatever that is construed to be? Should certain forms of content be privileged over others? Should radio be made by professional elites or by neighbors and community members? And the question that hovers above them all: Who gets to decide?

The history (and future) of radio shows us that these contests don't necessarily settle down once and for all. Though the commercial network model was largely ascendant by the 1930s (and became much more concentrated after The Telecommunications Act of 1996), advocates for other uses mounted challenges on many occasions, and succeeded in carving out some room for alternative models more than once. Most recently, in 2000, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) started issuing licenses for "low-power FM" (LPFM) radio stations; this represented a marked change, as no new low-watt licenses had been issued since 1978. This shift in policy didn't come out of nowhere, though. In fact, the FCC was responding to not only pressure from advocates of "microradio" (as it was often called during the 1990s), who publicized the issue through high-profile pirate broadcasting and court cases, but the FCC's own observation of the effect of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which left no doubt about the chilling effect of corporate media consolidation on localism.

Why would we even want hyper-local FM stations? FM can still do a lot of things, even some that other media technologies can't. It's easily accessible to listeners, cheap and easy to program, and a great tool for people to reach out to others in their neighborhoods or towns with local, original content. It's resilient, too -- in moments of tragedy and disaster like Hurricane Katrina, radio was a far more durable and reliable communications infrastructure than networked computing, not least because receivers and transmitters can run off batteries and generators. Even an apparent disadvantage of radio -- the scarcity of airtime -- can be a plus, in that it prompts groups to make thoughtful decisions about how to use their stations.

Until now, LPFM stations have been permitted only in rural and suburban areas where already crowded airwaves didn't preclude them. As a result of intense lobbying by the likes of Clear Channel and even National Public Radio in 2000, LPFMs had to conform to conservative spacing requirements (called third-adjacent channel spacing), which meant that in cities and dense media markets, new stations couldn't go on the air. The new legislation seeks to remedy this by opening up more space on the dial by permitting a slightly less conservative metric to be used. The result of this change will be more stations overall, including the addition of some LPFMs to the airwaves in suburbs and many cities, which means that different sorts of community groups and audiences will have access too.

The LPFMs that have gone on the air since 2000 have flourished. Radio in rural areas can be unexpectedly powerful partly because high-speed internet rollout has lagged there. Nearly everyone has radio receivers, especially in their cars; car receivers are in fact better and stronger than household sets and can pull in weaker or more remote signals. But it's not just the "digital divide" issue that gives radio staying power. Or rather, it's more complicated than that. As mentioned above, FM radio got a boost after Katrina because it was a reliable communications network, which distinguished it; a good number of new LPFM stations have worked out special arrangements with their local law enforcement to try to stay on the air and give people local, current information in case of disasters and emergencies (in contrast to a situation that unfolded in Minot, ND in 2003). A specific example of this is an LPFM station in a Florida farmworker community, where physical dispersal as well as literacy and language issues can present barriers to other means of communication. For many farmworkers, English is a third and Spanish a second language after an indigenous mother-tongue, so their local LPFM station was indispensable as it provided workers with up-to-date information about sheltering from Hurricane Wilma, as described in this worker's testimony before the FCC. Significantly, the radio station was not only giving out information; as the testimony indicates, people could call the station with information on the ground and with questions, in effect creating dialogue between the station and its listeners that allowed rescue workers to better respond to needs in the community.

This past decade has shown what people can do with LPFM in America's countryside. The opportunity to build more stations in cities and suburbs will permit a further reimagining of uses for LPFM in different, though still highly local contexts. One feature that is likely to carry over, however, is the use of the stations for intra-community dialogues and exchanges of information. Another is the voices on the air being your neighbors, who could be spinning Bhangra or bluegrass, holding interfaith discussions, giving out traffic reports or information about community health initiatives, and everything in between. Curiously enough, some features that are touted as being integral to new media--like the collapsing boundary between producers and audiences--can also be found in this use of radio.

Why hasn't the Local Community Radio Act passed yet? One main reason is Congressional dysfunction; nobody in Congress truly opposes its passage, and President Obama has indicated he will sign it into law. But it's also on the top of no one's agenda. No one wins elections based on their support for low-power FM radio.

There is plenty of information about the bill and its timeline for passage here. And if you're convinced about low-power FM, see if your Senator supports it.

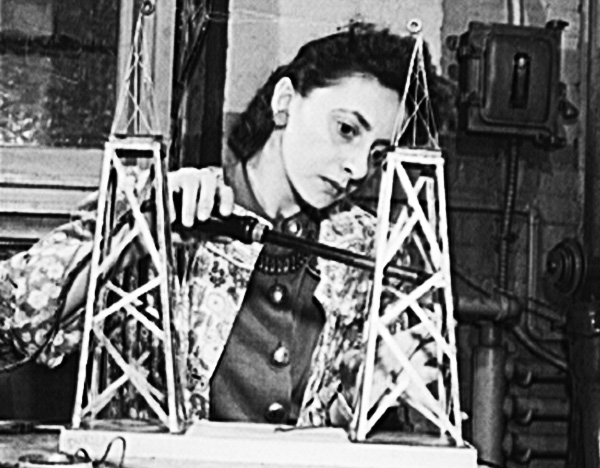

Images: 1. Library of Congress; 2. National Archives.

Further reading:

Susan Douglas. Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Susan Smulyan. Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Thomas Streeter. Selling the Air: A Critique of the Policy of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Eric Klinenberg. Fighting for Air: The Battle to Control America's Media. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007.